Subscribe to our E-Letter!

Subscribe to our e-mail and stay up-to-date with news and resources from street vendors around the world.

Home | Human Impact Stories | Stability sought for massive Nepal bazar

Water surges from Tukucha Khola river during Kathmandu’s summer monsoon, flooding the packed-earth floor inside the huge Bhrikuti Bazar. Then in the spring, high winds damage the bazar’s tarp and bamboo roof. Both natural calamities entail huge expenses for the 700 vendors renting 1,400 stalls.

Since the bazar was established in 1993, the vendors have asked their landlord, the federal government’s Society Welfare Council, for a permanent structure with roof and floor.

“Sometimes they’ve even started the process, then the minister stops it. This is due to political instability,” said Hemraz Acharya, the bazaar’s leader for the Nepal Street Vendors Union (NEST), which advocates for the rights of vendors. “We once even had a budget allocated, but then the minister changed.”

Each year, they’ve resorted to building a temporary wall to stop monsoon flood. “Last year we spent between $8 and $9,000 USD,” said Hemraz. This amount is borne by the vendors on top of their monthly rent of 3,010 NPR per stall, which includes closed-circuit TV, electricity and WiFi. They pay extra for security and drinking water.

“The government isn’t interested [in constructing a permanent market], but we will keep asking,” said Hemraz.

Their ask also includes drinking water and longer-term leases on stalls. Leases are signed annually. NEST, which is affiliated with the General federation of Nepalese Trade Unions (GEFONT), wants proper contracts running five to 10 years. “This would be more stable,” said Hemraz, 50. “It’s a long-term issue.”

Negotiations are often uneasy. Several years ago, the government increased rent based on the promise of improvements that never happened.

The market’s redeeming feature is that business is thriving.

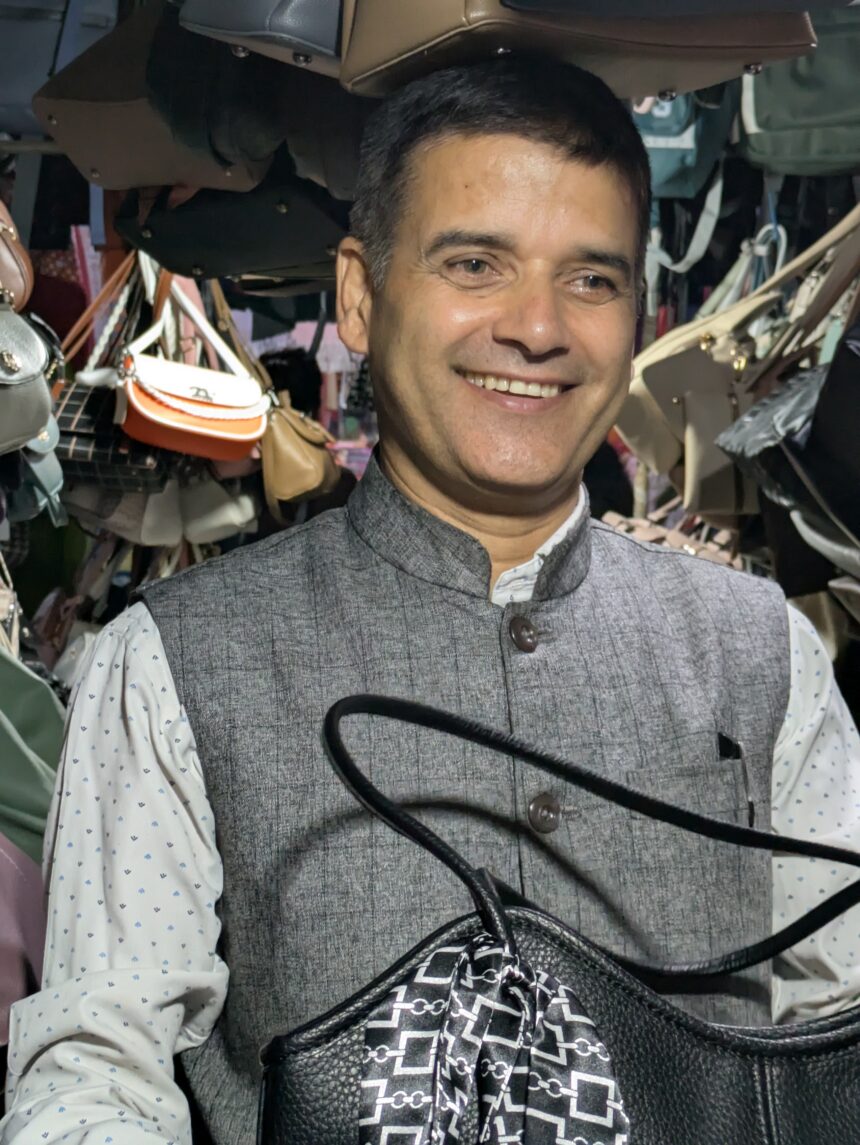

“Customers feel secure here because we provide good service,” said Hemraz. Vendors sell everything from fabric to clothing, towels, blankets, beauty products, electronics, bags, toys and more.

Hemraz and his wife have been selling ready-made gents wear for 27 years. He is from a rural area but was studying in Kathmandu where some of his brothers were vendors. They encouraged him to become one too. About 97% of the city’s market vendors are from outside Kathmandu Valley. Hemraz has since grown a family: his daughter, 20, is doing a diploma in IT, and his son, 14, is in grade nine.

When Hemraz joined NEST in 2011, his first role was recruiting market vendors. NEST, which began in 2003, now has 200 members in Bhrikuti Bazar and 12,400 members across Nepal.

Hemraz, who dresses as a gentleman in a white shirt, buttoned-up vest and grey slacks, shakes hands and greets many vendors as he walks through the market.

Bhrikuti Bazar, which is strategically located near Kathmandu’s central bus stations, is the city’s largest; it’s known locally as Hong Kong bazar because most of its goods used to come from China or Hong Kong. The bazaar is huge; it has seven entrances and takes some 15 minutes to stroll one end to the other. A temple is under construction in its centre; there is already a pond, rest area for vendors and two meeting buildings.

Another active vendor, Lila Prasad Oli, has been a member of Bhrikuti Bazar’s management committee for 15 years. One of his roles is to help sort out any customer issues. “Customers are integral to the sustainability of the market,” he said. As we sit in the smaller meeting building, the PA announces that a customer’s lost property has been turned in. “We do everything we can to provide good service,” said Lila.

The market management committee also allocates stalls, and brokers payment for drinking water and electricity.

Both Hemaz and Lila gained skills for their work through numerous training sessions in management, public speaking, recruitment and more. NEST offers these in conjunction with StreetNet International, which promotes the rights of vendors in 50 countries.

Before moving to Kathmandu, Lila, 57, was a farmer in Dolakha: “There was plenty of food, but no hard cash. It’s better to be a vendor.” He has been a vendor at this market 38 years, beginning at its previous location10 minutes away. Politicians ordered them to vacate that property, and they settled on this government-owned land; the tourism office is located behind Bhrikuti Bazar.

Lila and his wife, who sell baby clothes, have two children, a son, 31, who is studying in Canada with his wife, and a daughter, 35, who is an elementary school teacher.

In addition to being on the market’s management committee, Lila, is also serving his second term as the elected NEST provincial member of Bagmati Province (which includes Kathmandu and has 1,100 members). He reports vendors’ problems to NEST and works to establish legal policies, including contracts and registration, that will protect them.

Hemraz, who is the secretary of NEST’S Bagmati province, and a NEST central committee member, works with Lila and the market committee on negotiations with the market’s landlord, which are ongoing.

“NEST acts as a bridge between the government and the market,” said Hemraz. “We are hopeful that we will get longer contracts eventually.”

About the author of this story: Barbara Sibbald is a Canadian journalist whose work includes articles on HIV/AIDS in Swaziland and Manipur, India, and drug resistant TB in Mumbai, India.

By entering your personal data and clicking “Suscribe,” you agree that this form will be processed in accordance with our privacy policy. If you checked one of the boxes above, you also agree to receive updates from the StreetNet International about our work